Creative software is largely sold as a service. Subscriptions are the default. Cloud accounts are expected. AI features are bundled whether you want them or not. Even basic tools increasingly come with usage limits and renewal cycles.

Against that backdrop, Inkscape feels almost out of place.

It hasn’t repositioned itself with trendy language. It hasn’t tried to compete in the AI arms race. And it hasn’t changed its licensing story to “free, but…” Yet despite all of that, or perhaps because of it, it continues to grow quietly inside professional workflows.

That raises a more interesting question than why Inkscape is free:

Why do people keep choosing it even when paid tools are readily available?

To answer that honestly, you have to start with the market context it operates inside.

Understanding the Market Inkscape Lives In

Graphic design software is no longer a niche category reserved for agencies and studios. By 2025, the global market sits at roughly $9.3 billion, driven by digital-first businesses, product design teams, marketing operations, educators, and independent creators.

Within that market, vector graphics are foundational, not optional.

Logos, icons, UI elements, brand assets, diagrams, and SVGs for the web are still the backbone of visual communication. And unlike newer creative categories, vector design isn’t growing explosively, it’s growing steadily, at around 8–9% annually. That steadiness matters, because it signals maturity.

Mature markets value reliability over novelty.

This is where Inkscape’s position becomes easier to understand.

| Context | Reality in 2025 |

| Vector tools | Core infrastructure |

| Pricing pressure | Increasing for individuals & small teams |

| Inkscape license | Free (GPL) |

| Adobe Illustrator | ~$260–$300/year |

For large agencies, Illustrator’s cost blends into overhead.

For freelancers, educators, nonprofits, and small businesses, it is a recurring decision that must be justified year after year.

That pressure doesn’t explain everything, but it explains who first looks elsewhere.

And once you look at who is actually using Inkscape today, the old assumptions start to fall apart.

Who Uses Inkscape

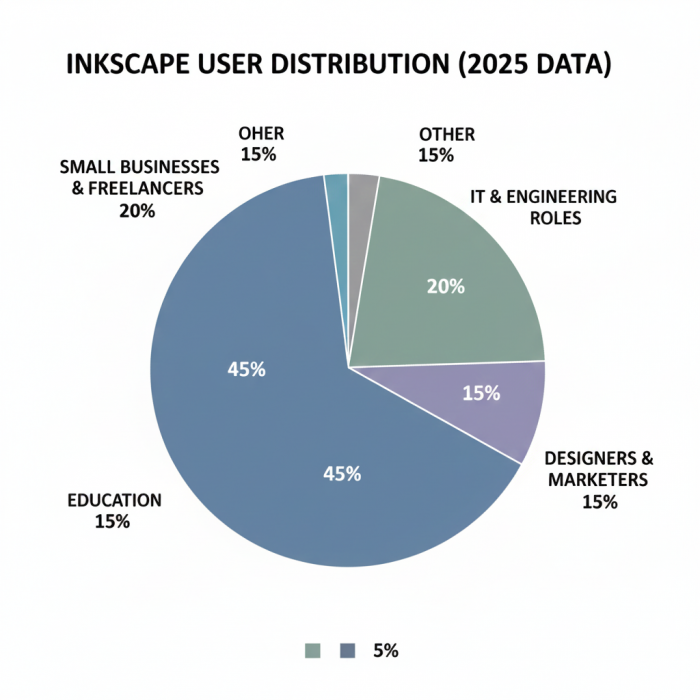

Inkscape still carries a legacy label as a “hobbyist tool.” That label doesn’t align well with current usage data.

User sentiment consistently sits around 88% satisfaction, and the nature of complaints is telling. Most criticism focuses on workflow familiarity, not output quality, things feel different from Adobe tools, menus are structured differently, shortcuts don’t map one-to-one.

In short, the friction is cognitive, not technical.

The user base itself has shifted in visible ways:

- A large portion comes from small businesses and solo professionals

- Strong adoption in IT services, engineering, and education

- Designers and marketers increasingly use it alongside paid tools rather than as a replacement

And when you look at what people actually do with it, the picture becomes very practical:

- Vector illustration: ~72%

- Logo and brand assets: ~58%

- Web graphics and SVGs: ~45%

These are not experimental use cases. They are production tasks.

Which leads naturally to the next question:

Has Inkscape kept up technically with professional demands, or is it surviving on goodwill alone?

How Inkscape Has Evolved Without Making Noise About It

Modern Inkscape effectively begins with version 1.0 in 2020. Before that, progress existed, but it was uneven and slow. Since then, development has become noticeably more focused.

By the 1.4.x release line in 2025, Inkscape no longer feels like a tool trying to “catch up.” It feels like a tool that has made clear decisions about what it wants to be.

A big part of that clarity comes from its relationship with SVG.

Inkscape treats SVG as a native format, not a compatibility layer. Files are fully W3C-compliant, human-readable, and portable. There’s no proprietary wrapper, no silent metadata bloat, and no dependency on a single vendor’s interpretation of vector data.

For web developers and UI teams, this honesty matters more than it gets credit for.

Interoperability has also improved in grounded, practical ways:

- More reliable handling of .AI files

- Improved .CDR imports

- Predictable PDF round-tripping

It’s not flawless, but it’s reached a point where many experienced users now describe import/export reliability as non-negotiable, not optional.

Performance improvements tell a similar story. Recent updates moved heavy path operations to NumPy-based internal computations, which shows up immediately when working with dense illustrations, technical diagrams, or maps. Tasks that once lagged now complete cleanly.

These aren’t flashy upgrades. But they’re the kind that professionals notice quickly.

Which raises a bigger question:

How does a tool without a corporate roadmap sustain this level of progress?

Community Health as a Signal of Long-Term Stability

Commercial software is evaluated through revenue, growth curves, and market share. Open-source software survives on a different metric: sustained contribution.

Inkscape has been in continuous development for over 21 years. That alone filters out most short-lived projects. But longevity isn’t the only signal.

- Contributors are globally distributed

- No single company controls direction

- The interface is translated into 90+ languages

That last point matters more than it sounds. In many regions, Inkscape is not an “alternative”, it is the only accessible professional-grade vector tool available.

In real workflows, Inkscape rarely stands alone. It’s commonly used alongside GIMP and Scribus, forming a complete open-source creative stack. That ecosystem reinforces trust and longevity.

Yet even with this maturity, Inkscape makes some very deliberate omissions.

What Inkscape Intentionally Does Not Compete On

Inkscape does not try to compete on:

- AI-generated design

- Prompt-based workflows

- Cloud-first collaboration

- Automated brand systems

Tools like Adobe Firefly exist because many users value speed and automation, sometimes at the expense of control.

Inkscape’s priorities are almost the opposite:

- Offline-first operation

- No background data collection

- Files you fully own

- Predictable, standards-based output

For some users, this feels behind the curve.

For others, especially educators, regulated industries, and long-term projects, it’s exactly why they trust it.

And that contrast explains where Inkscape ultimately lands in 2025.

The Takeaway: Inkscape as Infrastructure, Not a Substitute

Calling Inkscape a “free alternative” undersells what it has become.

It is better understood as open infrastructure for vector graphics, a reference point built on standards, longevity, and accessibility rather than feature races.

For small businesses, educators, NGOs, and professionals who prioritize precision and file ownership, Inkscape is no longer a compromise. It’s a deliberate choice.

Once you view it through that lens, the real question changes.

It’s no longer why Inkscape still exists in 2025.

It’s why more creative tools aren’t built this way.

Post Comment

Be the first to post comment!