When I first opened Suno AI, I wasn’t trying to replace a studio, a musician, or even a hobby. I just wanted to see whether an AI could feel music the way humans do. That curiosity is exactly how Suno has pulled in nearly 100 million users globally, by lowering the barrier between an idea in your head and a finished song playing in your ears.

But by 2026, Suno is no longer just “fun.” It’s controversial, powerful, emotionally addictive, and sitting uncomfortably between creativity and copyright.

This is not a feature checklist. This is what it feels like to actually use Suno, daily, repeatedly, sometimes excited, sometimes frustrated.

From Text Prompt to Full Song: Why Suno Feels Different

Most AI tools generate parts of music. Suno generates songs, vocals, melody, structure, and sometimes even emotion. Typing a few lines into the prompt box on suno.com/create and hearing a complete track in under a minute feels borderline unreal the first time.

What stands out immediately is the voice. Suno’s vocals don’t sound robotic in the obvious way earlier AI music tools did. They breathe. They slide between notes. Sometimes they even crack slightly in ways that feel unplanned. That’s why reviews across Product Hunt and Reddit threads like this honest community discussion keep repeating the same phrase: “This shouldn’t sound this human.”

The Numbers Behind the Hype

Suno isn’t a small experiment anymore. Following a $250M Series C round in late 2025, Suno AI reached an estimated $2.45 billion valuation, with backing from heavyweight investors like Lightspeed, Matrix, Menlo Ventures, and Nvidia. That level of capital doesn’t fund curiosity projects, it funds infrastructure, legal defense, compute at massive scale, and aggressive growth targets. Revenue estimates in the $150M–$200M ARR range explain why pricing tightened sharply in 2026: unlimited experimentation does not coexist well with GPU-heavy inference costs and enterprise-level compliance pressure.

At this scale, Suno is no longer judged like a creative tool, it’s judged like a music platform. When millions of songs are generated daily, the question isn’t whether any single output infringes on copyright, but whether statistical similarity across billions of generated melodies begins to resemble the catalogs of existing artists. That’s why copyright issues stop being abstract. Training data provenance, licensing disclosures, and usage rights suddenly matter not just to lawyers, but to users deciding whether a song is safe to publish, monetize, or even upload to platforms like Spotify.

Scale also changes user dynamics. Early adopters treated Suno like a playground. In 2026, a growing percentage of users treat it like a production tool, which raises expectations around reliability, version stability, and predictable licensing. A glitch that once felt like a novelty bug now feels like a workflow disruption. Likewise, restrictions that make sense from a business perspective, such as pay-to-download or non-rollover credits, feel harsher when users are emotionally invested in songs they consider “their own.”

In short, Suno’s success forced it into a different category. It’s no longer compared only to Udio or Soundverse, it’s implicitly compared to parts of the music industry itself. And once a tool reaches that level of influence, every creative decision becomes a legal, economic, and cultural one, whether the company intends it or not.

The Trust Question: Can You Actually Rely on Suno AI?

From a technical standpoint, Suno is reliable. Songs generate fast, often under 60 seconds using the v5 model. The mobile apps on Google Play and the Apple App Store are polished, with ratings around 4.8–4.9 stars, which is unusually high at this scale.

But trust isn’t just about uptime. It’s about what happens to your music.

Free-tier users in 2026 can generate songs but cannot download them, and commercial usage is explicitly restricted. Many negative reviews on Trustpilot stem from this shift—people felt blindsided when features they relied on quietly moved behind a paywall.

Suno is trustworthy as a tool, but not generous anymore.

The Controversy That Won’t Go Away

The biggest shadow over Suno is copyright. Major labels, UMG, Sony, and WMG, have filed lawsuits questioning whether Suno trained its models on copyrighted recordings without permission. This is covered in depth by industry analyses like Production Expert’s breakdown and long-form critiques such as this AFB review.

Suno’s response has been to shift toward licensed-only training datasets for future models. That’s reassuring, but it also means:

- Older generations may carry legal uncertainty

- Commercial users must read the fine print carefully

- Spotify and other platforms may reject uploads if rights are unclear

Spotify, Distribution, and the Uncomfortable Middle Ground

Suno-generated music is not banned by Spotify, but it’s not explicitly endorsed either. Uploads are evaluated like any other track. The risk isn’t detection, it’s ownership. If you upload a Suno song commercially without the correct plan, you’re assuming liability.

This is why professional musicians often say Suno is “fun but not sleep-losing”, it inspires ideas, but it doesn’t yet replace a legally clean workflow.

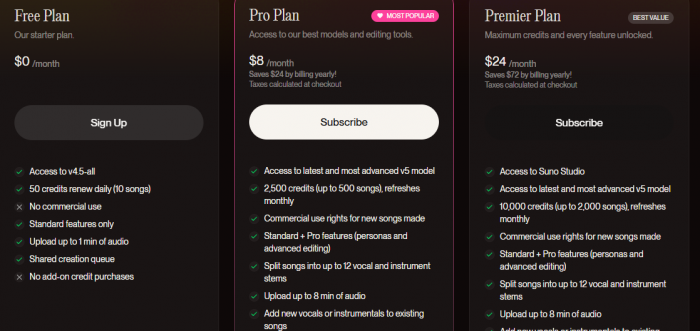

Pricing: Where Friction Starts

The pricing page at suno.com/pricing explains the structure clearly, but using it feels different than reading it.

- The free tier feels like a demo now

- Credits don’t roll over, which creates subtle pressure

- Running out mid-project is frustrating in a very human way

Pro and Premier plans unlock stem separation, longer tracks, and commercial rights, but they also make Suno feel less like a playground and more like a subscription responsibility.

Creative Highs and Technical Lows

When Suno works, it’s intoxicating. Genre blending, like “ambient Hindi pop with lo-fi jazz undertones”,is where it shines. The Continue feature helps extend songs, but it also exposes one of Suno’s quirks: the “60-second curse”, where tracks end abruptly unless carefully managed.

Mobile users report freezes and occasional “vocal hallucinations” when prompts become too complex—something echoed in reviews on platforms like Eesel.ai and Beatoven’s comparison.

Emotional Reality: Why People Keep Coming Back

The most interesting thing about Suno isn’t the technology. It’s the feeling of instant creative validation. You type lyrics. You hear them sung. No rejection. No waiting. No awkward silence where an idea usually dies. The distance between imagination and output collapses into seconds.

That experience hits something very human. For many users, especially those who never had access to studios, instruments, or collaborators, Suno removes the quiet friction that usually stops creativity from becoming sound. Ideas that would have stayed in notebooks or voice notes suddenly feel real. Heard. Finished.

That power also carries a subtle risk. Because Suno never says “no,” it trains the brain to expect constant creative reward. Each generation becomes a small dopamine loop: tweak the prompt, regenerate, try again. The music improves, but so does the attachment. People don’t just generate songs, they start caring about them.

For casual creators, this feels liberating. There’s no gatekeeper, no technical barrier, no judgment. For professionals, the experience is more complicated. Suno feels like a sketchpad that works astonishingly well, but always with an asterisk, questions about ownership, originality, and long-term safety quietly sit in the background of every good result.

That unresolved tension is what defines Suno in 2026. It’s not just a tool you use; it’s a system that reshapes how people relate to creativity itself. And once someone experiences that immediacy, it’s very hard to go back to slower, more uncertain ways of making music.

Final Reflection

Suno AI is not just a music generator. It’s a cultural signal. It shows how close we are to a world where ideas turn into artifacts instantly, and how messy that transition is.

You can trust Suno to create music.

You should question it before monetizing that music.

It’s brilliant, controversial, imperfect, and emotionally compelling, all at once.

Post Comment

Be the first to post comment!